Conscious of the fact that theirs was only one of several hundred similar bombers, all flying an identical course in a great invisible corridor in the sky, the pilot and gunners strained to catch a glimpse of other aircraft. Suddenly out of the corner of his eye the pilot sighted a line of white specks some distance to port; at once the mid-upper gunner reported a bomber being attacked by a night fighter. Not waiting to watch the result of the attack, the pilot started to fly an erratic course, corkscrewing gently so as to provide a more fleeting target for any other fighter that may be stalking his Lancaster from astern. There was no further call from the gunner and the crew took comfort in the belief that perhaps the bomber managed to evade the German fighter.

Five minutes later the radio operator passed a further wind broadcast from home to the navigator, who told the pilot that the Lancaster was crossing the German coast, a fact confirmed on the H2S. Crossing in near Hamburg, the coastline easily recognised at this point, Berlin was still an hour’s flying time away. The German fighter assembly beacon nearby was passed, but another assembly point was not far distant to port of the bomber stream. At this stage there was little flak and no searchlights penetrated the cloud below.

Suddenly a great burst of light exploded ahead and above the Lancaster, casting a weird, flickering glow on the surrounding cloud tops and momentarily lighting the cockpit. Someone in the crew reported a ‘scarecrow’; a pyrotechnic thought to be fired from the ground to simulate an exploding bomber. It transpired that no such devices were ever fired by the Germans during the was and it was likely that these explosions were either bombers exploding, or large flares dropped above the bomber stream by German reconnaissance fighters.

The gunners now started calling in to report tracer being fired at aircraft on both sides of the Lancaster, which was still weaving gently from side to side. The mid-upper broke off suddenly in mid-sentence and then called urgently to warn of a single engine fighter sweeping in from the rear quarter. As the pilot banked sharply towards the attack, he was immediately aware of minute shafts of light passing close ahead. There was an angry clatter of gunfire from the mid-upper. Five seconds later the gunner reported that the fighter had disappeared. Pilot and flight engineer anxiously scanned their instruments to spot any telltale loss of power or pressure and there was a quick check of crewmembers on the intercom. Fortunately the fighter had overshot the Lancaster and disappeared.

Events now occurred in swift succession as the navigator warned the pilot that the target was only ten minutes away. The bomb aimer reported that he had completed his Window dropping and was taking his position at his bombsight. At this moment the rear gunner reported another aircraft closing in from astern, but the pilot, sensing rather than seeing cloud towering ahead, warned the gunners to hold their fire in the hope of evading the enemy fighter. There was a brief clattering sound from somewhere aft and then the Lancaster was swallowed up in the grey shroud. The pilot banked the aircraft sharply one-way and then the other. Moments later the Lancaster emerged from the towering cumulus and the bomb aimer reported that he could see the ground ahead. The crew was conscious of a vibration that passed right through the Lancaster, and the mid-upper called back to report sparks streaming back from the starboard outer engine. The flight engineer reported a loss of power on the engine and that its coolant temperature was climbing fast. A fire warning light flickered on. The vibration was getting worse and the pilot ordered the engine to be stopped. The flight engineer immediately switched off the Merlin’s master fuel cock, operated the fire extinguisher on that engine, feathered the propeller and switched off.

As the pilot re-trimmed the aircraft to counteract the drag from the stopped engine, he was aware that there had been no further word from the rear gunner and, receiving no reply to a check on the intercom, ordered the mid-upper gunner aft to find out what had happened. The Lancaster was approaching the target area, and with the flak intensifying there seemed less chance of being attacked by enemy fighters. The climax of the flight approached, as the bomb-aimer reported that he could see the first target indicators. All around the ground was a sea of flashing explosions, among the countless pinpoints of white twinkling incendiaries huge shimmering bowls of fire erupted as the huge blast bombs shattered the streets far below.

As he had to keep the Lancaster steady on a straight course, the pilot completed his final trimming as the great bomb doors were opened, causing a slight nose-up tendency. These were the most hated moments of the whole flight as the crew sensed that every German gunner on the ground was aiming at their own aircraft as it flew up to the point at which it released its deadly load of bombs. Making his own fine control corrections on the auto control, the comb aimer was oblivious to the noise and chaos about him as the Lancaster rocked from the explosions of nearby shell bursts. Suddenly the great bomber seemed to be lifted by some invisible hand. ‘Bombs gone’, came the call from the bomb aimer. Still the pilot had to maintain a steady course for some moments until the photoflash recorded the impact point of thebombs.

The all-important photograph taken, the navigator passed a new course to clear the target area. The mid-upper gunner reported to the pilot that the rear gunner had been slightly wounded in the arm, that the oxygen supply to the rear turret was no longer functioning and that the turret was partly jammed. He assisted the gunner forward into the fuselage and gave him a portable oxygen set. The pilot ordered the mid-upper to remain in his turret and told the radio operator to help the wounded gunner further forward and attend his wound.

Although the Lancaster was perfectly capable of maintaining altitude on three engines, the crew was painfully aware that it still had a long flight home. With the airspeed reduced to about 160mph indicated and a strong headwind, it would be covering enemy territory at only about 120mph. Experience on previous raids suggested that the German night fighters had concentrated their efforts upon the bomber’s approach to the target, and that only occasional attacks were made on the returning stream. Nevertheless, aware that his defences had been severely reduced, the Lancaster’s captain warned the mid-upper to keep a sharp lookout for other aircraft. The bomb-aimer volunteered to keep watch astern. The navigator passed a new course for base.

Time passed slowly. Soon the Lancaster was again flying over unbroken cloud. After eight hours in the air there was a perceptible lightening in the east as dawn approached over eastern Germany. The pilot ordered the bomb aimer forward to his position in the nose as the navigator reported that the H2S showed the aircraft to be crossing the Belgian coast. The radio operator called up to say that the wounded gunner had lost a lot of blood and, though conscious, was in some pain despite a morphia injection. Calling for a course to steer for Manston, the pilot decided to make for the nearest diversion airfield to get medical help for the gunner as quickly as possible.

Another ten minutes passed and the bomb aimer reported that the cloud was breaking up below. Easing back the throttles, the pilot started descending towards the Kent coastline. Still he dared not break radio silence in case there were enemy intruders over south-east England awaiting the bombers’ return.

At 4.30 it was already beginning to get light. At 5,000 feet the bomb aimer called up with a sighting of the coast. The pilot now called Manston for permission to land, stating that he had a wounded crewmember aboard. The airfield replied, giving landing instructions; the huge runway was quite adequate even for a Lancaster without brakes.

With the runway lights in sight, the pilot started a wide circuit to the left, thereby keeping the two good port engines on the inside of his turns. Lowering of the undercarriage caused a slight nose-down trim change, but this was corrected with selection of 20 degrees of flap. Keeping the speed at about 140 mph, the pilot turned onto the approach about two miles from the runway with plenty of power. Now he eased off throttle to reduce speed to about 125 mph, gradually winding off the course rudder trim and maintaining his heading by use of rudder. Once over the runway threshold at about 50 feet, he selected a bit more flap and firmly eased back on the control column. As the Lancaster touched down at about 90mph the flight engineer closed the throttles and the pilot started applying the brakes. The great bomber slowed rapidly and the engineer shut down the remaining outer engine for taxying on the inner Merlins.

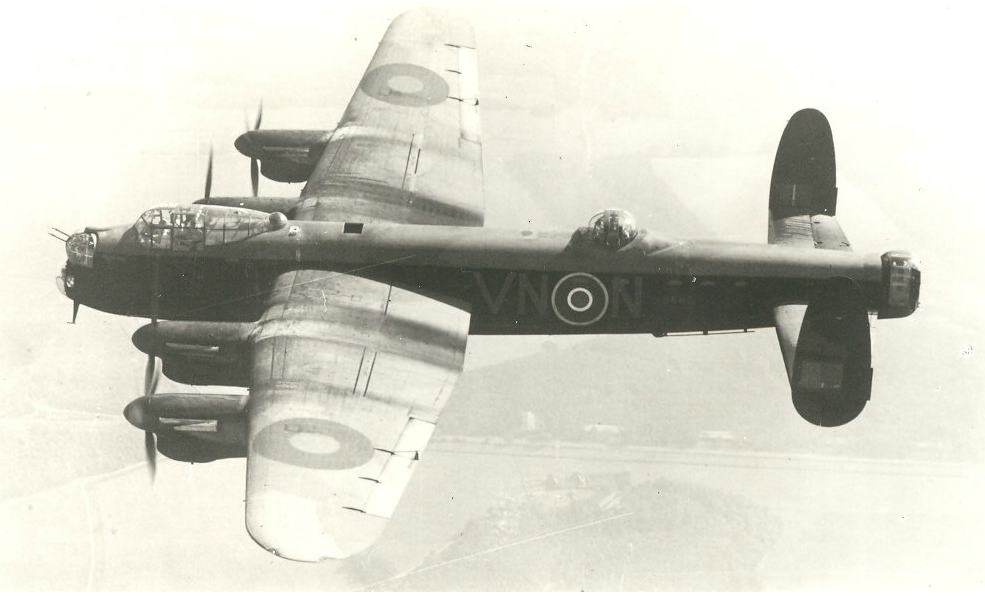

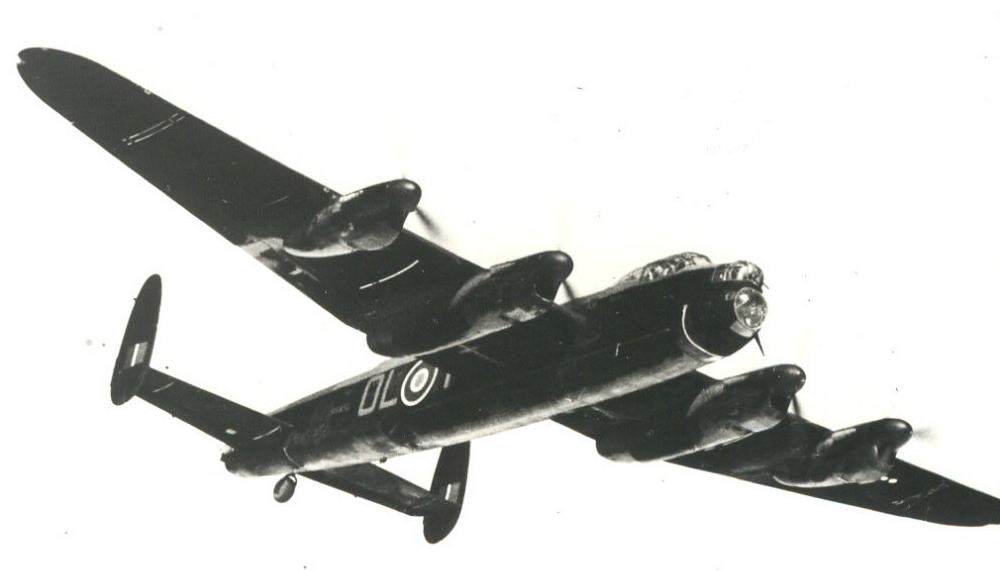

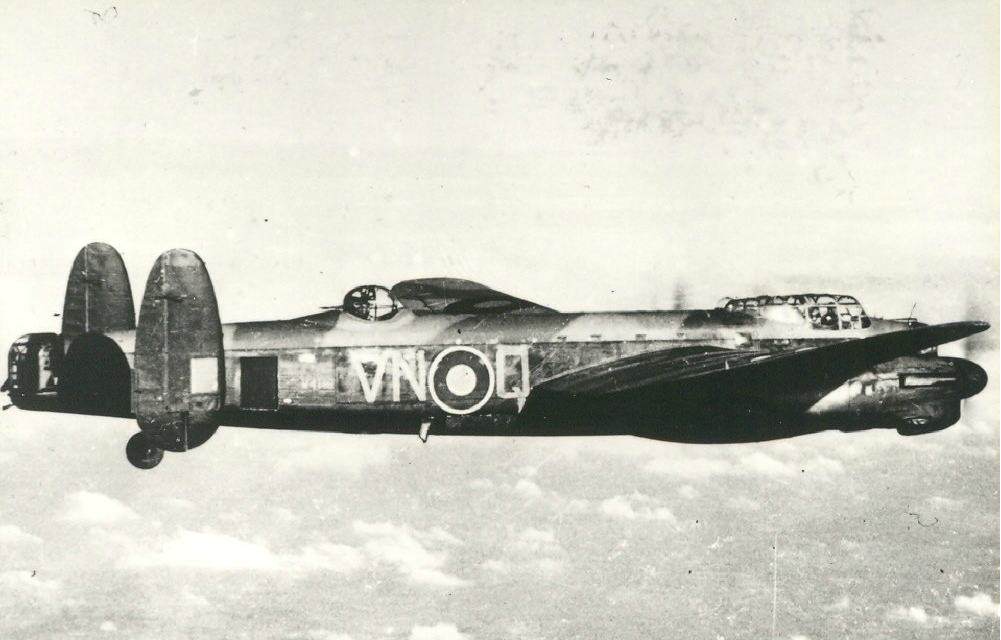

The Lancaster (courtesyhttp://www.ixb.org.uk/lancaster3.htm)