Richard Edgar Peter Brooker war history

Richard Edgar Peter Brooker

Richard Edgar Peter Brooker. Born Chessington. Surrey. 1918. joined the Royal Air Force on a direct commission in April 1937. on the 17 July 37 he was posted to 9 F.T.S. Hullavington. Wiltshire. and on the 19 Feb 1938 was Posted to 56 Sqd Royal Air Force North Weald. Essex. Promoted to Pilot Officer 05 April 38.

Promoted to Flying Officer 05 January 40. He claimed a Ju 87 destroyed on the 13 July 40 and a Do 17 on the 21 August 40, in this engagement he was hit by return fire and was slightly injured in the forced landing at Flowton Brook. Bramford. Suffolk. His Hurricane P3153 was burned out.

Late summer 1940.

Posted to Central Gunnery School. Sutton Bridge as an instructor.

Promoted to Fl Lt 05 January 41 April 1941. Posted to command No 1 Sqd. Royal Air Force Kenley.Surrey.

10 May 41. He shot down an He 111, at night, also attacking three more bombers on the same sortie. Awarded D.F.C. 30 May 41.

03 Nov 41. Posted to the Far East.Kallang.

13 Dec 41. He took command of 232 Sqd. after the C.O. was killed on 20 January 42 at Royal Air Force Seletar Singapore.

On 01 February 42 the squadron withdrew to Palembang. Sumatra.

25 Feb 42. 232 Sqd evacuated to Java, the remnants of 242 Squadron were absorbed into 232 squadron at Tajililitan. Java.

Promoted to Sqd Ldr 01 March 42.

05 March 42 some 7,000 Royal Air Force personnel moved from Poerwokerta to the port of Tajilitjap. South Java for ship transit to Adelaide.

Where they arrived on the 15 March 42. After the last Hurricane was destroyed on Java, S/L Brooker and a number of pilots flew in a Lodestar to Australia.

27 March 42. He was awarded the bar to his D.F.C. Personnel Management Agency. Royal Air Force Innsworth. Gloucestershire.

Confirm that as of 01.04.42 Sqd Ldr R.E.P.Brooker. Special Duties List - to command 77 Squadron Australia on loan to Royal Australian Air Force.

New Zealand Defence Force Personnel Archives show 18.06.42 disembarked New Zealand. Posted to Masterton. Air Headquarters.And 19.06.42.- Special Duties List - flying on loan to Royal New Zealand Air Force.

18.06.42.- Special Duties List - flying on loan to Royal New Zealand Air Force. where he is reported as Officer Commanding. 14 Squadron Royal New Zealand Air Force.

July 1942-Feb 1943.

Officer Commanding. 14 Squadron. Royal New Zealand Air Force. Masterton. New Zealand. flying Kittyhawks He formed this squadron from the survivors of 488 Sqd Royal New Zealand Air Force, who also fought on Singapore, Sumatra and Java, and who had flown Buffaloes and then Hurricanes.

15 Feb 43 posted to Whenuapai. Air Headquarters. On his return to the U.K.10 April 1943 and with seven and a half enemy aircraft shot down, he was posted to command No 1. S.L.A.I.S. at Milfield, as Wing Commander Flying, posted across the airfield as temporary Officer Commanding 59 O.T.U. Milfield, then joining F.L.S. as a Staff Instructor, O.C. Armament Wing. May 44 posted Wing Leader 123 Wing. 83 Group. 2nd Tactical Air Force. Royal Air Force. Thorney Island. Hampshire. (198 and 609 Squadrons) and led the wings Typhoons through the D-Day landings. 01 December 44. Awarded the D.S.O. posted Wing Leader 122 Wing. 83 Group. 2nd T.A.F. At Volkel.(B80) Holland.

While at S.L.A.I.S. he met Sqd Ldr John Wray, who was attending as a course member, their paths were to cross again later and the Milfield connection came into play again when John Wray became Wing Commander Flying of 56 O.T.U. Having relieved Wg Cdr John Wray at Volkel.Holland as Wing Leader of 122 Wing. 2nd T.A.F , his wing was comprised of five Squadrons, No`s 3, 56, 80, 274 and 486. In the six months from the Normandy landings, 06 June 44.

The wing lost 123 pilots and in the first month of 1945 they lost 47 pilots.

It was from Hopsten (B112) that Wg Cdr Brooker took off, leading a section of Tempests of 80 Squadron, on the 16th of April 45 to patrol the Hanover - Osnabruck sector with the attack priority, rail traffic, after attacking a train near Neuruppen, and while the section were re-forming his No 2 advised him that there was smoke coming from his radiator, followed by flames seen in his cockpit, the Wg Cdr was seen, to be trying to open the canopy, before the aircraft turned over and plunged to the ground. His No2. Sgt W.F.Turner. was, at the same time, shot down by FW 190`s both aircraft crashing and burning close by the autobahn at Wittenberge. He was awarded his second D.S.O. (bar) sometime after this. Dated the day before his death. Wing Commander R.E.P. Brooker.D.S.O. and bar., D.F.C. and bar. is remembered on the Runnymede Memorial, Panel 264.

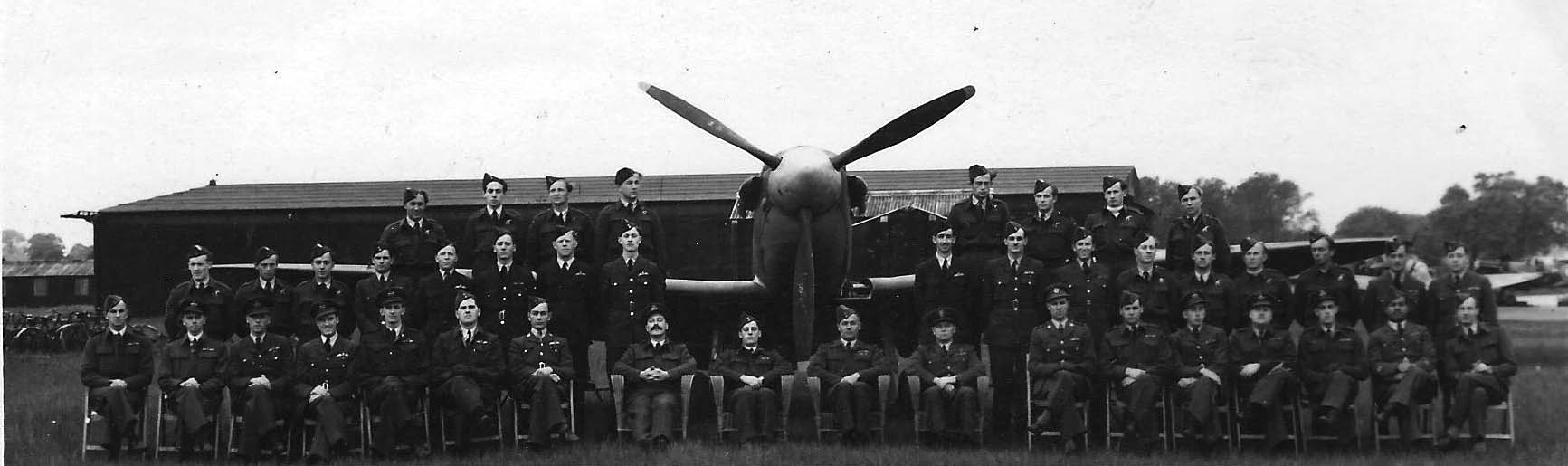

Believed to be Flying Training School Hullavington 1937. REP Brooker seated extreme left.

1940.

“Founded in June 1916, the Squadron (motto on the badge of the 56th Persuit :- ‘quid si coelum ruat = what if the Heavens fall’) went overseas in the following April. Arriving in France at a time when the German Air Force was making a strong bid for supremacy, No 56 soon established itself in the forefront of Fighter Squadrons. Most feared by the enemy, its history is one of brilliant records of achievement, and many of the greatest British Air Fighters of the war learnt their technique while serving with No. 56. The Squadron is now located at North Weald, Essex.” from Players cigarette cards

“There were two other Squadrons, Nos. 17 and 151 based at North Weald....... our day at North Weald started with a working parade on the station parade-ground at 8.30, where officers and men of all three Squadrons assembled before marching to work. Most of the morning was taken up with routine inspections of aircraft and there was little flying done before lunch, which was taken at 12.30. Occasionally we had a ‘Lunch Day’, a special institution which enabled pilots to travel to any other aerodrome in the country on the pretext of a routine cross-country practice flight, but which was, in reality, a social call. Most of the flying during the day consisted of interception, attacks with one flight simulating a force of bombers, and formation flying,. This was practiced over and over again.

Between 56 and 151 there was an intense spirit of rivalry. The latter complained, perhaps with some justification, that 56 thought a little too much of itself....... the fact remained that in many ways we were inclined to be faintly patronizing.

Each Squadron tried to assert its superiority in a number of ways... 151 would stage a practice formation flight of six machines designed to end spectacularly over the Mess.. in an impressive breakaway with each machine ‘peeling off’ in tight formation.

The next day 56 would attempt an even more elaborate demonstration with the whole Squadron. Flying in still tighter formation, they would break away in sections, each section leader performing a neat loop while the outside men pulled up in stall turns to either side. Little comment was made in the Mess on these displays .... ...

The Commanding Officer, S/Ldr Knowles, known as “Teddy” to his contemporaries,, and as “The Fuehrer” to us, was a strong, silent man of the type so often seen pacing the bridge in a film drama of the sea. Off duty in the Mess he was a very different man. It was said he was a Bachelor of Music but he only revealed his talent occasionally .. although a strict disciplinarian, S/Ldr Knowles hated red tape. No one could have studied more closely the interests of his pilots...... Next in seniority came F/Lt Joslin, who commanded ‘A’ Flight, of which I was a member. He was a large man with ginger hair and a ginger temperament. He drank enormous quantities of beer with no apparent effect, had a huge laugh, a charming wife, a spaniel, but never any cigarettes. He was killed in action (?1941) during the first week of his command of 79 Squadron.

The rest of the ‘A’ Flight was composed of F/O Roger Morewood, F/O Richard (Klondyke, or just plain Klon) Coe, and P/Os ‘Fish’ Fisher, ‘Boy’ Brooker, Wicks, Harris and myself ... The Squadron had the usual collection of cars in various stages of decrepitude, ...(Richard) sold the ancient Norton motorcycle which he had hotted up sufficiently to be summoned for exceeding 80mph on the Epping Road (“just seeing what it would do”) and bought a car .... we instantly christened it ‘The Barouche’ ... an ancient Renault.... a modification was to adapt the carburetor to run on paraffin. Petrol was expensive and the idea was to fill the main tank with petrol for starting only. He had to abandon it for various reasons, not the least of which was the additional unwelcome attention the Renault attracted on account of frequent backfiring with belching of flames and black smoke. ... we found out later that the practice of running a motor on paraffin is illegal........ Wicks and Brooker, apart from myself were the most junior officers in the flight and were naturally the most inexperienced pilots, although both had done considerably more flying on Hurricanes than I had done.

.....Brooker was to his great disappointment posted from the Squadron and made Personal Assistant to the then Air Officer Commanding Training Command. In the short time he held the job he created something of a sensation. The story goes that while flying the Great Man’s personal machine one day, luckily without a passenger, he turned off the petrol instead of on to the reserve supply and had to force-land with a dry carburetor. Shortly after this he managed to get permission to fly a Hurricane, also belonging to the A.O.C. While amusing himself with a few aerobatics, one of the gun panels on the wing fell off as he was half-way through a slow roll, hitting the tailplane and severely damaging it. Brooker was luckier in making a forced landing this time. I feel sure he was not sorry to rejoin his Squadron again. (Soon after he became C.O. of No 1 Squadron) “ from The Way of a Pilot by Barry Sutton

C/O at Northweald at that time was Wing Comdr F.V. Beamish (D.S.O.), a great and inspiring leader, (officially reported missing in combat 1.4.42) Peter was still stationed there at the outbreak of War, 3rd September 1939

13th May 1940 he took the post of personal assistant to Air Vice Marshall Park at Uxbridge

56 Squadron pilots summer 1940

20th June 1940 he was posted back to 56(F) Squadron with which he remained through the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940

F/O Bryan John Wicks, 56 (F) Squadron, aged 20, was Peter’s best pal at the time. ‘Willy’ Wicks went missing for two weeks in May/June 1940. (story in appendix)

On the 18th August 1940 the official ‘bag was 144. Peter was wounded in action on 22nd August 1940 whilst bringing down a Dornier 17 near Ipswich and was listed in the Roll of Honor published by the Air Ministry 31st August 1940 among the wounded or injured in action. Luckily it was nothing too serious - his head had been jerked forward and he sustained a bad cut to the bridge of his nose and a couple of black eyes. On his return home, with a plaster over his nose, he told his mother he had had a ‘rough night!’ During the Battle of Britain the fighter pilots continued to destroy great numbers of enemy aircraft - their greatest ‘bag’ being 235 officially destroyed on 15th September 1940.

1941

In May 1941 the Germans made 71 major raids on London and 56 on other cities. On Sept 17 1940 Hitler postponed the invasion of Britain indefinitely - following the Battle of Britain.

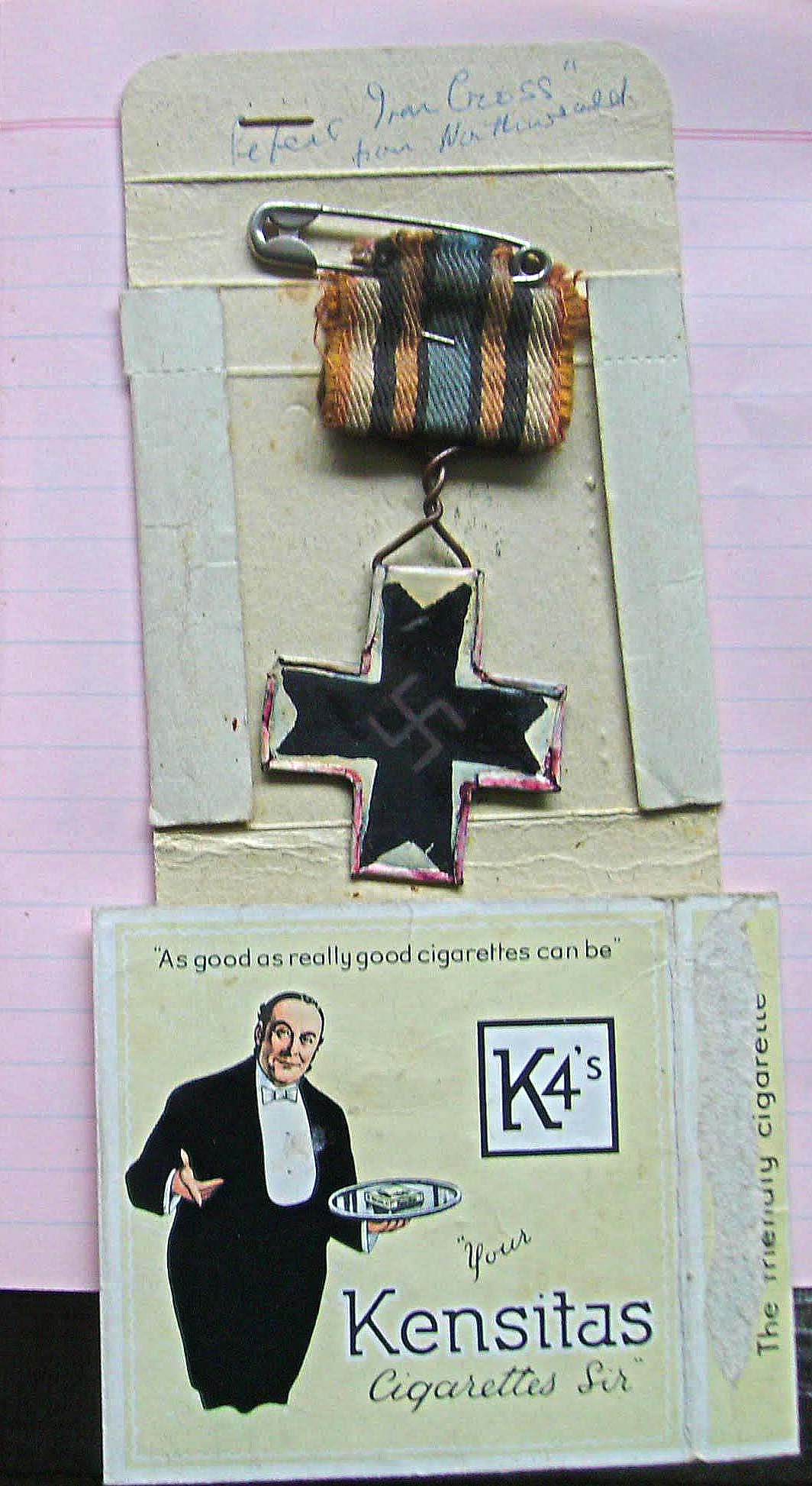

Peter remained with 56(F) Squadron, at North Weald, (Station Commander S.F. Vincent) becoming Leader of ‘A’ flight until 23rd April 1941. He was officially promoted to Acting Squadron Leader on 20th April 1941. On leaving he was presented with his most appreciated medal - given to him by Bryan, Willywix’ on behalf of the lads left behind in the old 56 Squadron . The presentation case, a Kensitas cigarette packet, contained a crudely made ‘iron cross’ suspended from a piece of deckchair canvas from a large safety pin. Peter seemed to value this higher than official awards.

Photo below: this spoof Iron Cross was presented to Squadron Leader Brooker in April 1941, on his promotion and posting to lead 1Sqn(F) at Croydon. It was given to him by Bryan Wicks (Willewix) and was a momento from all his old comrades who had fought together on 56 Sqn at Northweald. The presentation case, a Kensitas cigarette packet, contained a crudely made 'iron cross' suspended from a piece of deckchair canvas from a large safety pin. Brookers family state that he valued this higher than any of his official awards.

23rd April 1941 - Squadron Leader Brooker takes over No 1 (F) Squadron at Croydon.

“...after a short stay in Redhill where, in May, they (No.1 Squadron) they really did experience a spot of excitement. In this month the attacks against England by the night bomber were stepped up as Hitler, moving his forces to the West, tried to hide his intentions and also sought to inflict greater damage on the one set of people who had rocked the power of the Third Reich. In the biggest raid, that of May 10th/11th, a total of 550 aircraft were employed, each making more than one sortie - if lucky - to drop 708 tons of HE and 86,700 incendiary bombs. But the other night fighters really got in amongst the bombers and destroyed over 30 of them.

No. 1 Squadron move to Redhill at the end of April and do some very successful night flying against the enemy during very heavy attacks on London. On the night 10th/11th May 1941 Peter’s squadron destroy 8 out of a total of 33 enemy night raiders - the highest ‘bag’ for night fighters.” from “ In All Things First”, a short history of No.1 Squadron

Peter informs us on May 18th that he has been awarded the D.F.C.

“Acting Squadron Leader R.E.P. Brooker, No 1 Squadron - This officer led his flight with considerable skill and ability over a long period, during which he destroyed a number of enemy aircraft. Since taking command of the squadron, he has greatly assisted in the brilliant work performed by the squadron. Throughout Squadron Leader Brooker has set an excellent example.”

Peter moved to Tangmere with No 1 (F) Squadron about 6th July 1941..

“In July they moved back to Tangmere and here they found many of the station’s old comforts were represented by just heaps of rubble and broken windows; relics of the days of not so long ago, and for some time the personnel had to sleep out at Goodwood, an arrangement which did not ease the work of the squadron disciplinary N.C.O., F/Sgt E.Stone, but which was just one of those minor inconveniences of war. Here the two Flights ‘A’ and ‘B’ worked on a ‘24 hour on and 24 hour off’ basis, and the ‘erks’ had few moans as they achieved the tasks given them

From Tangmere they switched to the offensive, and the Operational Record Sheets soon began to carry many entries under the headings of numerous operational code words.” (from In All Things First, a short history of No.1 Squadron)

29th July 1941 ‘The proudest day in the Brooker family’. Peter decorated by King George VI with the D.F.C. at Buckingham Palace. Bryan Wicks also decorated with the D.F.C. at the same ceremony and the two families join forces afterwards for lunch and a show in celebration.

From Tangmere he was posted overseas (Far East) on 1st November.

Sunday 9th November 1941 Peter leaves home destined for G.H.Q. Singapore. He went as Aide de Camp to Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke Poppham, C in C far East. ‘News becomes very scarce owing to the serious situation in the Far East. Japan and America at war on 8th December. We receive three letters from Peter at Kallang Aerodrome Singapore.’

1942

Extracts from”Bloody Shambles” (see appendix)

Tuesday 6th January:- In a belated attempt to curb the series of training accidents and to boost confidence within the ranks of the untested and untried Buffalo pilots of 488 Squadron, Sqn Ldr R.E.P.Brooker DFC, a Battle of Britain veteran, arrived at Kallang from Air H.Q., and promptly led both flights on a convoy patrol. Three Blenheims of 34 Squadron also carried out shipping escort duties during the day.

Tuesday 20th January: This day was to see the heaviest yet raid on Singapore... .... at Seletar the Hurricanes were ready to go into action and great things were expected of them ....Sqn Ldr Landels was fatally wounded and his aircraft struck the mast of a fishing vessel before crashing into the sea..... the Hurricanes were having mixed fortunes .. despite the attack bombers continued to their target - Seletar - but failed to cause much material damage on this occasion. Flt Lt. Farthing assumed temporary command of 232 (P) Squadron following Landels death ..... by evening however a new commanding officer had been posted in - the experienced Sqn Ldr Brooker arriving from Air H.Q.

Wednesday 21st January:- (Japanese attacked Kalang) Sqd Ldr Brooker, had led eight Hurricanes from 232 Squadron’s ‘A’ and ‘B’ Flights into the air at 1055 in anticipation of the raid, and these were vectored onto three streams of bombers, Brooker leading them down into a diving attack. As the Hurricanes closed on the bombers, they were joined by more aircraft from ‘C’ Flight, led by Flt Lt Cooper-Slipper. As the latter approached they saw one bomber spiral down in flames, the victim of Flt Lt Taylor’s opening attack; NAP I/C Tadashi Hino and his crew were killed. Closing in, Cooper-Slipper opened fire on another bomber, hitting its port engine which caught fire, and it turned over and lost height. Throttling back, he turned into another vic of bombers, causing a second to break away in flames, some bullets striking the engine. He then came under heavy cross fire and his aircraft was hit many times, some bullets striking the engine and three hitting the aircrew, he broke away and despite the damage to his machine, landed safely at Kallang. ..........

Friday 23rd January:- After lunch Sdn Ldr Brooker led four Hurricanes off on patrol, during which Plt Off Parker saw a lone twin-engined aircraft pass below, and was suprised when the leader took no action. Within minutes Parker saw six fighters climbing up towards them, but was unable to radio a warning to Brooker, so pulled alongside him and pointed to them:-

‘They were in the usual loose formation used by Japanese fighters, and Brooker immediately went after their leader. I was a bit astonished at this but I had allowed some distance between us so that, when as inevitably happened, the second Jap followed him, I was in position to latch on to the tail. The first one turned smartly to port and we all four followed because I also had a ‘Zero’ behind me. I concentrated on aiming at the one ahead of me. Brooker must have realised the mess we were in because, just as I saw my shots hitting my target’s tail, he led us out of the ring into a steep dive.’

Meanwhile the other two Hurricanes, flown by Plt Off Bill McCulloch and Sgt Fairburn, had become involved with the Japanese top cover, McCulloch having claimed one shot down and Fairburn a probable before they managed to extricate themselves from the action. The quartet, having reformed, was now beset by fuel shortage so they headed for Singapore, running into heavy cloud and rain which split them up again. McCulloch and Fairburn once more came under attack, the former being shot down into the sea just short of Kallang, he managed to bail out of BM898 and was later rescued, suffering only from shock. Meanwhile, Fairburn’s aircraft was out of fuel and he was forced to crash-land BE639 on Pulau Blakang Mati, sustaining minor cuts and bruises. Brooker and Parker reached Seletar safely but with fuel exhausted and problems with the hydraulics, the latter was obliged to belly-land BG820, escaping injury.....

Saturday 24th January:- ..the Hurricane’s scramble had been the second of the day. During the earlier one, Plt Off Parker (whose rest day it was) had an insight into the state moral was reaching amongst some of the airmen. He witnessed some of the ground crews leaving their posts, led by a Flt Sergeant whose nerve had clearly broken. These men had endured much hardship under attack and there were those who had reached their limits, as he recalled :-

‘They clambered into a bus immediately the Hurricanes had left, shouting to those last on board to buck up, or to the driver to ‘get cracking’. They were hesitating because they realised that no men would be at their posts to service any returning Hurricanes. The bus started to move away from me and the men climbed aboard, but it had to pull round in a U-turn in front of the office. I shouted to the driver to stop and, when he took no notice of my bawling and waving, I unbuttoned my holster and took out my .38 revolver, which all of us pilots wore, whether flying or not, at Singapore. I aimed to shoot into the air or at the tyres of the bus if it passed me. I was scared stiff because I knew I was far more likely to hit the bus than its tyres, but I was determined to find out more of this sudden departure of the ground crews. I had never known this to happen before. Anyhow, it was unnecessary for me to shoot as the driver hauled the bus to a stop and I called out Flt Sgt. He said they had permission from ‘Penny’ Farthing to push off from the airfield during air raids (which I doubted but could not contest) and that aircraft were nearly always away for more than an hour, which I knew to be true. I pointed out that the fitters, an armourer and a radio technician must be available to service any aircraft returning early, and he agreed hurriedly that four men should remain. He called them out and they appeared from the bus quite happily and looked rather unconcerned about remaining. I assumed that the Flt Sgt had influenced the men to rush off from the field but he himself was in a panic to get away and having agreed to let the rest go with him, I thought better of arguing the toss until a better opportunity might arise. So he lept back into the loaded bus and away they went. The four men who remained glanced around the sky before sauntering off to their workshops. Then I saw for the first time a Corporal seated on top of a blast-pen in the sun, quietly enjoying a mug of tea. I asked him what he was doing there and he replied that he had too much self-respect to go chasing off every time there was an air-raid, and he intended to stay there until it was obviously safer in a trench or shelter. I just grinned at him and said ‘good show!’

When the Hurricanes returned, having not made any contact with the raiders, Sdn Ldr Brooker was furious to find a lack of ground crew. The pilots and the skeleton ground crew began refueling the aircraft, for they intended to take off again. Parker agreed to see if he could find the missing crews who had exceeded their time limit. However, the cause of their delay was soon evident. Some of the bombs had fallen on a nearby village outside the main gate, also blocking the road. Parker was sickened by the sight and smell of burning bodies in the huts and was glad to get back to the airfield.

Sunday 25th January:- 232 (P) Squadron lost two more Hurricanes - and their pilots - this time due to adverse weather conditions. During the morning at 0955 Sdn Ldr Brooker and Sgt Marsh took off from Seletar, but when Brooker emerged from cloud Marsh in BE641 had disappeared. At much the same time Sgt Alan Coutie (BE589) took off from Kallang with others from ‘A’ Flight to patrol over the Island and he too disappeared in worsening weather with visibility down to 300 ft. Neither pilot was ever seen again, both, it was assumed, had crashed into the sea.

26th January 1942:- RAF attack against Japanese convoy approaching Endau ; included nine Hurricanes of 232 Squadron led by Sdn Ldr Brooker. ....... became involved in a series of dogfights, the sky appearing to the pilots to be full of Japanese fighters and burning Vildebeests.

Brooker selected the nearest Ki 27 while other pilots chased after the surviving Vildebeests, hoping to give them some protection. ....... all Hurricanes returned safely. Whilst the aircraft were being refueled and re-armed the pilots related accounts of their combats; consequently six of their opponents were assessed to have been destroyed; Sqdn Ldr Brooker, Plt Off Parker, Flt Lt Edwin Taylor and Sgt Henry Nicholls claimed one each, while Plt Off ‘Dizzy’ Mendizabal added a probable, and came across another Ki 27: “I must have suprised him, because he made no attempt to get away.

The fall of Singapore

27 January - 15 February 1942

Tuesday 27th January - The harassed RAF was given no respite. Early in the morning Sqn Ldr Brooker, Plt Off Parker and Sgt Christian took off in an attempt to intercept a reconnaissance aircraft, but failed to make contact after climbing to 25,000ft at that point Christian’s Hurricane suddenly peeled off and swooped all over the sky, losing height rapidly. Brooker called him on the R/T and went chasing after him but could see no reason for these antics, nor did he receive any reply. The chase was called off when the Hurricane disappeared through the low cloud blanket and Brooker and Parker made their way back to Seletar. At 1000 the Hurricane crashed at great speed into a small rubber plantation in Johore and exploded. Flt Lt Norman Welch, 232 squadron’s Adjutant, was in charge of a small party which went to the scene of the crash, where they had to dig to a depth of 13ft just to reach the tail of the aircraft. ....

Wednesday 28th January:- of the original delivery of 51 crated Hurricanes, 21 remained available for operations, with four more that could be made ready in 24 hours. Of the rest 17 had been destroyed, seven were at repair depots and two were still with their unit, but in need of repair. During the morning Sdn Ldr Brooker led all available Hurricanes to strafe the newly-occupied Kulang airfield, but found no aircraft there so strafed AA positions instead.......

Saturday 31st January:- .... 488 Squadron had at last got three Hurricanes serviceable again by the 31st but these were then handed over to 232 (P) Squadron and the unit ordered to leave. At the last moment the ground party was ordered to remain and service the Hurricanes still on the island, 232 (P) Squadron’s ground personnel being shipped out to Palembang instead. Next day Sqd Ldr Brooker was ordered to evacuate the majority of his Squadron, only he and five other pilots remaining.. ... During the 11 days in action 232 (P) Squadron had claimed 38 confirmed, 10 probables and 14 damaged for the loss of 18 Hurricanes during operational sorties. At least seven more had been badly damaged in combat, while two were destroyed on the ground. Nine pilots had been killed, and four seriously wounded.

from the Far East Command Communiqué:- Singapore, February 5th. There has been some enemy shelling in the north of the island, with negligible results. Air reports show much enemy movement southward in Johore. Enemy aircraft have continued to make high-level and low dive-bombing and machine gun attacks on the island, causing comparatively little damage or casualties. Shipping in the harbour was also attacked. An oil tanker at the naval base, which was set on fire two days ago by enemy bombing, is still burning. Hurricane fighters of the R.A.F. intercepted a large formation of enemy aircraft over Singapore this morning. one enemy aircraft was destroyed, one probably destroyed, and one damaged by our aircraft.

Thursday 5th February:- At Kallang 232 Squadron was warmly welcomed by Sqd Ldr Brooker and the remaining five pilots of 232 (P) Squadron, several of whom renewed old friendships, but the meeting was brief as Brooker and the others were about to fly to Palembang for a well-earned rest. There was no time or labour available to fit long-range tanks to the Hurricanes which were to depart, but the pilots were advised that a Blenheim would meet and lead them to Sumatra. Most could only stow aboard their personal kit, but Plt Off Parker did manage to include a 120 volt battery to power hi electric razor. as they taxied for take-off Sdn Ldr Brooker ran his aircraft into a bomb crater and was forced to remain behind. The other five were led off by Flt Lt Taylor ...... in the event however, their rest did not materialise and they were soon in action again over their new base.

“With the aerodromes of Tengah and Seletar under shell-fire and Sembawang vulnerable to it at any time ... there was only one place left from which we could operate. This was Kallang aerodrome, the former municipal airport of Singapore.... we were now ordered to move down there ........ taking our two Hurricanes and two automobiles. (The aerodrome at Kallang) was a sorry sight ..... the road entering passed under imposing dark stone archways, now pitifully scarred and chipped by blast and shrapnel and bullets. The beautiful hangars and terminal buildings of what had once been a great airline base were barren and empty, with windows gone, walls gashed and torn. The vast concrete aprons between and in front of the hangars here were torn and pitted with bomb craters, as was the entire field. The saddest sight of all was the remains of several Hurricanes and Brewsters, as well as three or four trucks and tank wagons, around the outside of the field - sorry-looking, smashed and twisted wreckages, mostly burned out, the victims of bombing and machine-gun attacks. .... The (Officers) Mess had been hit and set on fire by bombs the day before, and was completely burned out.” from ‘Last Flight From Singapore, by A.G.Donaghue

Saturday 7th February:- .. further aircraft flew out to Palembang during the day as they were rendered airworthy, including a Hurricane and Buffalo flown by Sqn Ldr Brooker and Sgt Kronk respectively.....

from the Far East Command Communiqué Singapore, February 7th:- Enemy aircraft again raided the island this morning and bombs were dropped, causing some damage. Fighters of the Far East Command intercepted the raiders, destroying one enemy aircraft, probably destroying another, and damaging two. All our fighters returned to their bases.

from the Far East Command Communiqué Singapore, February 8th. During enemy raids over Singapore island this morning our fighters probably destroyed one enemy bomber. Two other bombers were damaged. All our fighters returned to their bases.

from the Far East Command Communiqué Singapore, February 9th. An enemy force in strength succeeded in landing on the western shores of Singapore Island last night. They are being engaged by our troops. Fighting continues. Hurricane fighters of the R.A.F., supporting our troops successfully intercepted enemy raiders today, destroying three, probably destroying three others and damaging thirteen. In a later patrol our fighter aircraft wrecked an enemy truck during a road strafe.

“...a new order came through that night ... It had been decided not to risk losing all our Hurricanes at once, as we would do, should this, our only remaining aerodrome get bombed, or worse, come under shell-fire from the advancing enemy. Also there was a pressing need for more airplanes at Palembang.” from ‘Last Flight From Singapore, by A.G.Donaghue

from the Far East Command Communiqué Singapore, February 10. The enemy has maintained continuous dive-bombing and machine-gun attacks on our forward areas in the western sector throughout the day, as well as high-level bombing attacks by large formations of aircraft.

London, February 10 (AP) The Vichy radio broadcast today a Japanese communiqué saying that all British airdromes on Singapore Island had been captured.

Monday - Thursday 9 - 12 February Other new arrivals at P1 (Palembang) included seven of 232 Squadron’s Hurricanes from Singapore, led by Sqdn Ldr Brooker, while next day Air-Vice-Marshall Maltby, the commander of WESTGROUP, also arrived from Singapore to assume control. Unable, however, to find a suitable headquarters location o the island, he and Air Commodore Staton would move on to Java a few days later. The newly arrived Sqdn Ldr Brooker was briefed to lead off all available Hurricanes at midday on 10th, but one taxied into the MVAF’s remaining Dragon Rapide (‘19’), which was being refueled following a flight from Batavia; the twin-engined biplane sustained extensive damage to its starboard mainplane, which under the circumstances prevailing, was deemed irreparable. The Hurricane formation meanwhile, had seen nothing of note, while two pilots were forced to return early, sick and dizzy due to a shortage of oxygen bottles in their aircraft; owing to this serious shortage, one flight was not able to climb above 18,000ft.

Friday 13th February ... a dozen Hurricanes were off from P.1 seeking six Japanese ‘flyingboats’ reported by the Dutch HQ to have alighted near the north-east coast of Banka Island; these were in fact F1M floatplanes from the seaplane tenders Kamikawa Maru and Sagara Maru, which had been detached to operate from the island, at Muntok, the island had by now largely been evacuated by Europeans and natives alike. A careful search was made by the Hurricanes, but nothing was to be seen, and Sqdn Ldr Brooker led them back to Palembang, low on fuel. They had just landed when the JAAF returned to the attack. 29 Ki 43s from the 59th and 64th Sentais, with seven Ki 48s approaching. At this moment the seven reinforcement Hurricanes from Java arrived overhead, almost out of fuel, some were forced to land at once, but Wng Cmmdr Maguire and Sgy Henry Nicholls remained above to try and give some protection, and these two at once attacked the incoming raiders. .... with the Hurricanes engaged, the Japanese bomber crews were able to gain a number of successes when they attacked shipping in the river..... While the bombing and strafing was underway, three more Hurricanes from ‘A’ flight of 232 Squadron were prepared for takeoff and, during a lull, were scrambled - climbing into cloud. They were followed a few minutes later by Sqn Ldr Brooker at the head of several more fighters, which began a hide-and-seek fight among the low clouds. .... Sdn Ldr Brooker claimed a second bomber for his sixth personal victory of the war (four of which had been credited prior to his arrival at Singapore). One of the Hurricanes (BG693) failed to return, Plt Off Leslie Emmerton last being seen at low level over the treetops, being persued by several Ki 43s; .. he was killed

“Saturday February 14th ... our engineer officer and his men had been doing themselves proud in getting damaged machines repaired and new replacement machines fixed for combat. As a result we had eight airplanes that morning, less than a week from the time the Squadron’s equipment had been virtually wiped out.. >>>Squadron had gotten some new aeroplanes also and I believe they had a full twelve that morning. anyway, there were enough Hurricanes dispersed around the field at readiness to make an imposing show after what our squadron had been through. .....(after scramble and skirmish..)..we were told not to land back at Palembang. I headed down the railway from Palembang and soon reached () aerodrome and landed as ordered. .....The reason we were ordered down here was that Palembang aerodrome was surrounded by more than two hundred parachutists, dropped there while we were away on our patrol!

... one of our pilots was on the ground when the parachutists landed....’we saw they were dropping parachutists all over the jungle, scores of them, in a big circle all round the drome, about a mile outside it..... I expected they’d be closing in right away .. I rang up Operations and told them so they could warn you not to land here...a little later the phone was dead. Several squadron leaders and wing commanders were there at the time and they got all the personnel organised to defend the place. We took up positions along the road...I suppose there were a couple of hundred of us all told... nothing happened for a while. There wasn’t a sound coming from the jungle and w kept getting more and more tense.... Pretty soon we saw you chaps coming back (from sortie - Banka Strait) .. we knew you must be having a scrap of some kind. Then one Hurricane came in, streaming glycol smoke, and landed.,.. he’d had his radiator shot up then we saw most of you heading off south west, having heard Control warning you not to land here. But then we saw that two Hurricanes were coming back.. they came in and landed. I expected to see them picked off by snipers from the jungle.... however nothing happened.... they hadn’t heard the warning... you should have seen them move! I never in my life saw two chaps get back in their machines and take off so quick! Then, horror of horrors, ... in came four Hurricanes and landed! They were new reinforcements for us, being ferried up from Java, and of course they had no radios installed so they couldn’t hear the warning. As soon as they landed some of us piled into a car and tore out onto the field to warn the pilots. We told them to turn round and take off as fast as they could and go down to (x) aerodrome, but they all said they couldn’t. They didn’t have enough gas..... so there was nothing else for it but to get a petrol tanker onto the field and fill them up, hoping we had time... the jungle comes right up to the aerodrome on all sides... how conspicuous we felt working out in the open on those Hurricanes, knowing there were a couple of hundred or more Japs with rifles and tommy guns in that jungle! ...we got those four Hurricanes refueled in what I bet was an all-time record! ” from ‘Last Flight From Singapore, by A.G.Donaghue.

Netherlands Indies Armed Services Communiqué:- Batavia, February 16. Early Sunday morning a large-scale bombardment was begun on the Japanese fleet in Banka Strait. American, British and Netherland aircraft took part in these bombardments. In the Musi Estuary the Japanese transferred their troops into all kinds of small craft, sloops, motor-boats, rowing boats and other local material. The invaders then sailed into various rivers and creeks, continuously harried by our very low-flying fighters and bombers, which played murderous havoc among the thousands of invaders. Our losses in aircraft and men are not yet known, but it can be taken that they are considerably lower than the extent of the large action would make us expect.

The fall of Sumatra & beyond

The fall of Sumatra

Saturday - Monday 14 th - 16 February From P.1, Sqdn Ldr Brooker of 232 Squadron - together with several other pilots and non-flying personnel - had evacuated by road. The vehicles following theirs were ambushed however, and a petrol bowser overturned by grenade explosions; one airman.AC2 Hugh Kilpatrick was trapped under the bowser, whilst AC2 J.L.Duff sustained a broken leg and jaw; he was helped to one side of the road while Flg Off H.L. Wright 232 Squadron’s Engineer Officer, led a party to administer help to the trapped airman. Just then the Japanese attacked and Wright was killed. The trapped airman could not be released and later on an orderly crawled up under covering fire and injected him with a double dose of morphine.

On 15th February 1942 the Japanese hoardes take Hong Kong and force Singapore to surrender.

16th - 28th February The necessity for the Japanese forces to establish themselves on the new airfields in Sumatra ensured that the Allies were able to enjoy a few days of relative quiet in Western Java, where strenuous efforts were expended to form the scattered remnants of the RAF’s squadrons into some semblance of an air force. With Air Vice-Marshall Pulford and a number of senior officers missing, overall command of the RAF on Java passed to Air Vice-Marshall Maltby.... For fighter defence, two squadrons were to be reformed, while 232, 258 and 488 Squadrons were effectively disbanded ... 18 Hurricanes operational. These were now concentrated at Tjilitan in the new 242 Squadron under Sdn Ldr Brooker, with the flights commanded by Flt Lt Ivan Julian and Act/Flt Lt Jimmy Parker.

Friday 27th February Western Java, ... four of 242 Squadron’s aircraft were off again ... led by Flt Lt Parker. As they commenced the climb two of the Hurricanes broke away and returned to Tjililitan. With Sgt Dunn for company, Parker continued up to about 20,000 ft. Below them at about 17,000 feet they caught sight of a group of distant aircraft against the pale blue of the horizon They counted between 12 and 15 fighters, straggling along and apparently not having seen the two Hurricanes. As they dived onto the group, three of the Japanese aircraft started to dive and turn to port, whilst the others pulled round to starboard and up in a slow climbing turn. Parker kept after the first three and brought his sights to bear on the leader. he later wrote:

“I only needed a little deflection at our angle of approach and I’d have him. To my surprise when I pressed the tit I heard only a couple of rounds from one of my guns and the rest were silent. I didn’t know what had stopped them and nearly broke my thumb pressing the button, but they were no results in the half-dozen seconds it took to overhaul the Zero. I dived within a few feet of him and saw his helmeted head peering coolly around as I passed his tail and then went into a long dive away. That was a very well-disciplined pilot to have remained a target for so long in order that his friends could come round and take us, particularly when they would anyway have been told too late to save him if my guns had fired!”

Sgt Dunn, following his leader in the dive, hesitated before firing, having observed Parker not firing , fearing that he may have misidentified the Japanese fighters for Dutch Brewsters. “I continued my attack as a practice and I was close enough to see the ‘Flaming arsehole’, as we called the Nip roundel; I knocked chucks off one ‘Zero’ and continued to dive on by.”

Parker continued “I taxied the Hurricane straight down into the ulu in a furious rage, instead of leaving it by the Flight Office to be refueled and re-armed, and stamped back up to the dispersal hut to sound off about the inefficiency of the armourers. To my suprise Air Commodore Vincent was there with Sqdn Ldr Brooker, and he tore me off a hell of a strip for not having checked my guns and everything about the Hurricane before I’d taken off. Brooker looked very sympathetic and the other pilots were almost mutinous because we all relied on our ground crews, but we all stood and listened to his tirade. Evidentally he must have heard that we were not too confident of the Hurricanes because he swore they were a match for the ‘Zeros’, and to prove it he took one up and threw it about the sky. We were not impressed and had no enthusiasm ourselves for aerobatics, even if the raid was over, and then we had another talk from him.”

Meanwhile back at home:-

‘No news from Peter until 25th February when we learn he is safe in Batavia, Java. (Batavia, former name of Jakarta, city and sea port of N.E. Java) There is no proper officer’s Mess and Peter stays with a most hospitable Dutch family. (see his letter from Townsville, below)’

from”Bloody Shambles”:-

Sunday 1st March:- The initial landings on the beaches of north-western Java began .. Allied air units under orders to counter attack...... Flt Lt Julian led off a section of three Hurricanes of 242 Squadron from Tjililitan, to ascertain the exact position of the landings; they were followed by nine more led by Sdn Ldr Brooker. .... The Hurricanes met by intense AA and rifle fire from the transports and shore, made their first attack on the atap huts along the shoreline, these huts were left in flames. ....242 carried out two more attacks in the course of the morning, while nearly all Hurricanes suffered damage, mainly from shell splinters, although none were lost ....

”...I cant remember who, but one of the lads in this raid left his parachute behind and sat on a tin helmet as the best means of protection when all the trouble was coming up from below.”

Monday 2nd March; At Tjililitan, by early afternoon more Hurricanes had been made serviceable and Sqdn Ldr Brooker informed his men that the unit was to carry out a full-scale raid on Kalidjati. The operation was to be undertaken from the Dutch base at Andir, just outside Bandoneng, as the advancing Japanese were now only 30 miles away from Tjililitan. All available Hurricanes, seven aircraft, set off for Andir, closely following the C.O., who had the only aerial map of Java available. As they approached the airfield the experienced heavy, but inaccurate fire; the Dutch had obviously mistaken them for Japanese aircraft. Brooker, realising this, calmly led the formation around the airfield until the firing stopped, then all aircraft landed safely.

Even as the Hurricanes were on their way, a Japanese bomber formation - estimated to be 50 strong - was also heading for Bandoeng, comprising aircraft from the 27th Sentai escorted by 59th and 64th Sentai Ki 43s. Most of the bombers turned back due to bad weather, but the fighters of the 59th continued. They arrived soon after the Hurricanes had landed at Andir, when an air raid warning was sounded and four CW-21 bs of 2-VIG-IV were scrambled, followed by the last three Brewsters of 3-VIG-V. The RAF pilots soon witnessed a short, sharp engagement and one Dutch pilot was observed floating down under his parachute. This was the CW-21B Flight’s commander, Lt Boxman, whose aircraft had been set on fire at 15,000ft. As he baled out, his petrol-soaked clothes caught alight and, in an attempt to douse the flames, he refrained from pulling the ripcord for some 5,000ft. However, on reaching the ground he had sustained serious burns and would spend the next two years in hospital before making a recovery.

... Part of the 59th Sentai formation landed at Kalidjati on return from the mission, where a further attack by a lone Glenn Martin was noted during the afternoon. After a conference with his flight commander, Sqdn Ldr Brooker decided that he would lead a strike on Kalidjati that evening, enabling the Hurricanes to return under cover of darkness. at dusk, therefore, six Hurricanes set off (the seventh having become unserviceable), but as they approached the target Sgt Dunn saw a single fighter diving on them and shouted out a warning. The Hurricanes immediately went into a pre-planned defensive circle. Owing to the darkness the British pilots were unable to fire effectively, whereas the lone Japanese pilot was free to attack and aircraft he could get his sights on. consequently Sgt Dovell’s aircraft received a burst of fire into its starboard wing. Dunn, observing this, immediately opened fire as the Japanese aircraft disappeared into the darkness. Dovell was obviously in trouble so Dunn formatted on him, but neither pilot had noted the return course. Fortune was on their side, as Plt Off Gartrell joined them and led all three back to Andir safely. On arrival Sqdn Ldr Brooker made felt his displeasure that the two sergeants had not noted the course for their return to base, and had thus risked the loss of their aircraft.

Tuesday 3rd March In Java, there had been no let-up in the fighting, most of which occurred in the west. Early in the morning all seven RAF Hurricanes set off from Andir to attack Kalidjati again. Sqdn Ldr Brooker ordering Flt Lt Parker and Plt Off Mendizabal to remain above as top cover, while he led the rest of the squadron down to strafe. Their arrival over the airfield was greeted by light AA gunfire, the pilots observing large numbers of twin-engined aircraft lined up neatly and proceeded to strafe these. As no defending fighters appeared to be present, Parker and Mendizabal dived down to join in the attack, each raking a line of aircraft, at least one of which was seen to catch fire. Parker then concentrated his fire on a petrol bowser which also burst into flames. Before they were able to select any further targets however, several Japanese fighters appeared and Parker spotted one on the tail of a Hurricane. Closing from astern he opened fire, but it turned and attempted to get on his tail. As he had built up speed when diving to attack, he was able to pull away, but Mendizabal - the victim of the attack - was not so lucky, and his aircraft was badly shot up; he managed to get some miles from the airfield before he was obliged to bale out. A running fight developed as the Hurricanes sought to get away, during which three victories were claimed by Plt Offs Gartrell and Fitzherbert, and Sgt King. No further Hurricanes were lost, but nearly all were damaged and Gartrell was slightly wounded.

The presence of the Hurricanes at Andir had left Batavia unprotected and in their absence, the airfields at Tjililitan and Kemajoran had been bombed. Consequently, following the Kalidjati attack, ‘A’ flight was ordered to return immediately to the former base.

Wednesday 4th March Western Java - The only sustained Allied activity in the air involved the RAF Hurricanes, four of which were sent out at first light for the Sunda Strait area, where 2nd Division troops were to be attacked. Flt Lt Julian and Plt Off Gartrell peeled off to investigate a long column of horse-drawn transport and were fired on. They called down the top cover (Parker and Fitzherbert) then all four flew up and down a straight, tree-lined road several times with guns blazing, leaving it blocked with fallen horses and overturned carts - unpleasant work. As they pulled away Parker saw a single horseman racing towards a thicket - one burst was sufficient to cause his demise. The RAF pilots were eating sandwiches on the airfield later in the morning when they were ordered to fly back to Andir on a ;’permanent’ basis. It was decided that the ten moderately serviceable Hurricanes would carry out a strike on Kalidjati on the way, while two semi-serviceable aircraft would go direct to the new base. Those pilots not allocated aircraft were to travel by road , a 1942 Buick - recently acquired by Plt Off Cicurel, who had attached himself to the unit - being commandeered for the trip, while Sgts Dunn and Young offered to drive a large petrol bowser to Andir - an offer which was accepted.

On approaching Kalidjati, six of the Hurricanes were led down to strafe by Sqdn Ldr Brooker, while Plt Off Lockwood,2/Lt Anderson, Sgt Sandeman Allen and one other of ‘A’ Flight remained above as cover. Sgt Ian Newlands (Z5691) reported;-

“I strafed various planes on the ground but missed on taking off and he opened up on me with cannons and machine guns - four red balls in my rear vision mirror was an unforgettable sight - but I didn’t get hit.”

Unable to observe much from the height at which they were flying, the top cover pair of Lockwood and Anderson followed the others down. Bill Lockwood recalled:

“As Lt. Anderson followed me down. I met at around 6 - 8,000ft two ‘Navy 0s’ climbing As I went past them and was about to pull around, I noticed a transport of the DC-3 type below and a landing circuit. I dove in behind this aircraft and was about to open fire when I remembered a remark made by someone before we took off about there still being a few Dutch aircraft around and not to shoot down any Dutchman. I climbed slightly and to the right of the aircraft to check. I saw the ‘fried eggs’ on the wings. He also saw me and turned away to port with wheels and flaps down. I looked in my rear view mirror and saw two ‘Zeros’ on my tail. I made a hurried diving attack on the transport and went to tree-top level, heading I knew not where, but hoping Bandoeng. The Japs were close behind and firing. I weaved and put the throttle thought the gate. I had a slight speed edge. Flying straight and very low I flew south for some minutes and presently came over a range of mountains and there was Andir airfield. I landed and Lt Anderson did not come in. I never saw him again.”

The other top cover pair also engaged the Japanese fighters, which were caught at a height disadvantage, as Sandeman Allen remembered:-

“The ‘Zeros’ came in underneath and we had a simple target for the first few vital moments, after which we were so heavily outnumbered that we got into serious trouble. I was credited with two ‘Zeros’ destroyed, one probable and one damaged but crawled back to the aerodrome with 28 canon shell and 43 bullet holes in the machine (Z5584), and with slight wounds to my head and legs. I remember being given a cup of tea and I was shaking so badly it stirred itself! However, I took off in a fresh plane 10 minutes later so that I was able to recover my nerve.”

Most of the other Hurricanes returned with varying degrees of damage. Although saddened by the loss of the South African Neil Anderson (who was taken prisoner but died in captivity two days later), the pilots were jubilant for they believed that they had shot down seven of the intercepting fighters - two by Sgt Jimmy King to bring his score to five in three days, and one each by Brooker, Julian and Fitzherbert, to add to the pair already credited to Sandeman Allen. What the Japanese losses were in the air is not known, but their fighter pilots - apparently from the 22nd Air Flotilla - also believed that they had shot down five of the Hurricanes. On the ground one light bomber was destroyed by fire, with two more and one reconnaissance aircraft badly damaged, while one of each and one Ki 48 were damaged to a lesser extent.

By late afternoon the 242 Squadron pilots traveling in the Buick had reached Andir, where soon after arrival a message was received requiring a Hurricane to reconnoitre the road leading southwards from Kalidjati to Bandoeng, since Japanese forces had been reported advancing down this in strength. Flt Lt Parker was detailed to undertake this sortie, Plt Off Fitzherbert volunteering to act as escort. Whilst discussing the job in hand, a raid by Kanoya Ku bombers occurred, the majority of the anti-personnel bombs falling in the region of the main buildings and hangars, where one of the Dutch afdeling was housed. Immediately afterwards, Parker and Fitzherbert ran out to their aircraft, started up and taxied between the bomb craters to the end of the runway.

Taking off in a cloud of dust, they headed for the west end of the valley, when Parker realised that his wingman was signaling frantically for him to turn back to Andir. a quick check of the instruments showed that all appeared to be in order, but Fitzherbert continued gesticulating, stabbing his finger furiously downwards and then he swung his aircraft round and headed back for Andir. Parker followed suit and almost immediately the cockpit filled with glycol vapour. Anticipating the vapour cloud would increase and restrict his vision, he closed the throttle and glided down just short of the runway and to one side of it. With flaps still down from his quick take-off and the undercarriage up, he hit the ground just in front of a Dutch bomber which was being re-armed.

The Hurricane thumped into the tarmac and slid past the bomber and running men, with a tremendous clatter and clouds of vapour. Fortunately Parker was strapped in tightly and the aircraft did not turn over as it came to a stop, minus its flaps, airscrew, radiator and much of its underside. He switched off the engine and jumped out smartly, to be greeted by the Dutch groundcrew who shook his hands repeatedly. He realised they were thanking him for pulling away from them before hitting the ground - when in fact he had been rather more anxious not to have crashed into their bomb trolleys!

It transpired later - after the C.O. had collected him and driven him back to dispersal - that the Hurricane had been damaged by a bomb splinter during the raid and that Fitzherbert had seen the radiator streaming glycol but had been unable to warn him sooner as his R/T wasn’t working. The reconnaissance sortie was abandoned, due to the lateness of the afternoon.

The pilots again adjourned to the Savoy Honan Hotel in Bandoeng for the night, and during dinner, Sqdn Ldr Brooker announced that two Dutch transport aircraft were due in that night to begin evacuating pilots. In the first instance wounded pilots would accompany Wg Cmmdr Maguire and himself, while four more pilots could have seats - to be settled by drawing lots. On his departure Julian was to take command of the remaining pilots and aircraft. In the event, the evacuating aircraft did not put in an appearance that night.

Meanwhile, Sgts Dunn and Young had not yet arrived from Tjiliiltan in the petrol bowser, but they were on the way. The bowser had been loaded with pilot’s personal possessions, including a number of gramophone records. Their journey was anything but uneventful. They had set off with Gordon Dunn driving, and were shortly overtaken by army convoy, as he recalled :

“An army sergeant enquired of our destination and on establishing this, said he would drive back from time to time to make sure we were not in trouble. We continued on our way, quite uneventfully until we reached the mountainous area, when the engine started to overheat. Pulling into the side of the road near a paddy field, we found an old tin and with this gathered water from the field and refilled the radiator. Within a short while of recommencing the journey we came to a steep decline, at the bottom of which was a stream with a narrow bridge. As there was a matching steep incline on the other side, I decided to accelerate, aiming the vehicle at the centre of the bridge. I noted that the speed had reached 50mph when Tom shouted a warning. An old man with a donkey and cart suddenly appeared on the bridge. There was nothing I could do, so half expecting a collision, we careered across the bridge, missing the man and donkey but hitting the back of the cart, before shooting up the other side!”

Apart from the radiator overheating again, the rest of the trip was relatively uneventful until evening time. As they parked for the night a Dutch officer approached them with a request for some fuel for his car. After facilitating him they experienced difficulty in turning off the tap and lost about 100 gallons of fuel. In return for the petrol, the officer found them accommodation and placed an army guard on the bowser. Next morning however, they found that they could not communicate with the guard, who spoke only Javanese and would not let them enter the vehicle; they had to wait for the return of the officer before they could get underway. Andir was eventually reached without further mishap but not before they had noticed a stenciled warning on the side of bowser “This vehicle not to exceed 15mph” They were hardly surprised therefore, when they later learned that the bowser would no longer travel faster than 2mph! Their main regret however was that their gramophone records had practically melted away in the intense heat of the glove compartment where they had been placed!

Thursday 5th March Wng Cmdr Maguire and Sqdn Ldr Brooker spent much of the morning in Bandoeng, where they experienced great difficulties with Dutch officials. Since many of the senior officers considered that further resistance was useless, and were divided in their wish to surrender, or to assist the RAF in continuing the fight, pleas for assistance failed. However, when verbal threats were employed, supplies of fuel - but not oxygen - were forthcoming. Having failed to carry out the reconnaissance detailed for the previous afternoon, Flt Lt Parker - on this occasion with Plt Off Lockwood as escort - took off as soon as sufficient cloud had formed to offer some refuge should Japanese fighters appear. A few miles to the west the cloud layer actually covered the tops of the hills .........(an eventful trip) ... His return was enthusiastically welcomed by all, including the normally stolid C.O., for having seen him persued across the airfield by the hostile fighters, coupled with his delayed return, all had assumed that he had been shot down. Even Wg Cmmdr Maguire telephoned his congratulations on his return and on his shooting down the bomber. However, he was suprised to learn that Parker had not sighted any enemy troops on the road to Bandoeng...

Friday 6th March In the morning Tjilatjap was heavily raided again, this time by land-based bombers .... One of the missing Hurricane pilots returned to the fold during the morning when Plt Off Tom Watson unexpectedly arrived in Bandoeng with quite a story to tell following his crash four days earlier:-

I managed to crash-land, wheels up, in a rice paddy field not too far away from the Japanese. Apart from a small bump on the head I was O.K. I got as far away from the scene of the crash as I could, and as fast as I could, and then started my trek back. The Japanese were between me and Batavia and I suppose I rather advanced with them, trying to keep out of sight. I threw away my flying helmet, put dirt on my face and tried to look as much like a native as possible. However, I had two problems. one that I have been bald since my late teens and the sun gave me hell, and the other was we had no proper flying equipment and all I had on my feet were low shoes. However, I found an old native straw hat after the first day which kept the sun off my head but at night it rained and the mud in my shoes started to wear on my flesh so that my feet became somewhat raw. Most of the Indonesians were afraid of me but one young boy really helped me. He could speak some English. There was no food to be had, water I drank out of any place I could find it, and I didn’t dare go to sleep. Japanese patrols were about quite a bit and once I hid while they passed. I was lucky there was something like a haystack to hide in. The second day the boy walked with me most of the time and was able, by talking to other Indonesians, to ascertain where the Japanese were. It soon became obvious that I could not get back to Batavia and I headed for the hills. I eventually reached the Tjilitan River and crossed it downstream from where the Japanese were repairing the main bridge that had been destroyed.

Watson then met an elderly native who helped him put together some bamboo poles to form a raft, although it would not hold his weight it acted as a support for him in pushing his way across the river. He decided to make for Tjililitan and shortly after crossing the river saw a horse cart and driver, which he commandeered to take him to his destination. However, he soon met a Dutch cavalry patrol that had suffered some casualties, including their officer, and therefore they had spare horses. He joined up with them, when he realised they were also heading for Tjililitan:-

“My experience as a horseman was not great at any time, and galloping with them through the jungle was rather harrowing. I was dead tired and my feet were in poor shape. We finally reached the town in the hills at about the same time as the Japanese. An Australian army captain saw me and told me to get in his truck with him, which I did. He was heading for the mountains where what was left of the Dutch and Australian troops planned to put up some sort of last stand. I also vaguely recall that my Australian friend had the responsibility of blowing up bridges after we had crossed them, to impede the progress of the Japanese. We arrived at this mountain base at night. From walking and riding horseback I was very stiff and riding in the truck had not helped. My feet were so sore that when I got out of the truck I could not stand up for a while. Here I learned that Batavia had fallen and what was left of the air force had had established at Andir aerodrome at Bandoeng. A Dutch captain got me a car and driver and gave me a letter to his wife in Bandoeng. I must have arrived at his home about midnight. His wife took off my shoes, bathed my feet, gave me sleeping clothes and I slept the night there. In the morning she found me socks and two canvas shoes which weren’t exactly a pair but were more comfortable as they were soft. I then set off to fine 242 Squadron.”

On locating the squadron’s HQ in Bandoeng it was arranged that he should be driven to the airfield. Watson’s traumatic adventure was not yet over however, and was about to take a turn for the better, but first:-

“Sandy Allen was driving me to the drome at a good clip when a truck was pushed across the road and we crashed into it. I was through the windshield and received rather a bad cut on the forehead. I came to with three rather beautiful young Dutch women caring for me. I tried to have them take me to a civilian doctor, as I did not wish to be taken POW at this stage, which would most likely happen if I went to a military hospital. However, I did end up in one. I was given an anaesthetic and an Australian doctor operated on me. I was rather lucky not to lose an eye.”

Undaunted by its diminishing resources, the small RAF fighter contingent continued to operate, although from Andir the pilots could hear gunfire in the hills and watched Japanese aircraft patrolling over the fighting area. A rumour rapidly spread that the remaining Dutch Brewster fighters, fitted with extra tanks, were preparing to evacuate Java, their destination being Australia! The disturbing factor was that the few remaining Hurricanes were to act as decoys to allow them to get away unmolested. The rumour appeared to become reality when Wng Cmmdr Maguire - although totally opposed to such a plan , but being overruled by the AOC - detailed newly-promoted Sdn Ldr Julian (who had just been advised by Air Vice-Marshal Maltby that he was to take command of the unit following the decision to evacuate Sdn Ldr Brooker) to carry out the operation.

With only six Hurricanes now available it fell to the senior pilots to undertake the task. As soon as sufficient cloud had formed to provide some sort of cover, the Hurricanes took off in pairs. However, Sgt Jimmy King’s engine cut just as he had become airbourne and he was obliged to force-land in a swamp. His No 2 circled overhead and was relieved to see him emerge unhurt, but by this time contact with the other four fighters had been lost and his companion was forced to return to base.

Sqdn Ldr. Julian led the remaining four Hurricanes into cloud, the formation having evidently escaped notice by patrolling Japanese fighters. The section separated, Julian and Gartrell heading for the Lembang area whilst Parker and Lockwood flew towards Kalidjati, where they came upon three bombers. Parker gave chase to one of these, Lockwood going after the other two. The latter made a diving attack on the rear bomber, but gained no hits, then came up directly behind it and closed to 100 yards. Observing his fire hitting one engine, he concentrated on the other and both started to burn. as his windscreen was covered with oil from his victims damaged engines, he lost sight of the bomber and returned to Andir, followed shortly by Parker. The latter also claimed a bomber shot down and confirmed having seen that which Lockwood had attacked, burning in the jungle........... That afternoon the three serviceable Hurricanes were ordered to patrol the mountain area to the north of Bandoeng.... Jimmy Parker recorded:-

“I was getting a bit fed up with this. On the ground I was scared stiff of having to take off and I was suffering from ‘pink-eye’, not at all happy to look up into the sun. However, I was more ashamed to appear scared in front of the others whilst we had a fair chance of survival.”

...... Parker’s plane was hit but he landed safely.... one shell had exploded in his starboard fuel tank, badly damaging the wing root although not causing a fire. The tail unit was scored and tattered, and he could feel a jagged hole in his armour plate seat....... fortunately he had been wearing a Dutch parachute which had thick webbing crossing in the middle of the back, which had undoubtedly saved him from serious injury. A heavy calibre shell had pierced the armour-plating of his seat; most of the fragments of this and the seat were embedded in the webbing of the parachute. However, several pieces had penetrated his back, just to the right of his spine.

With the onset of nightfall three Dutch Lodestars and a KNLM DC-3 landed on a road near Bandoeng, to make one of the last evacuation flights out of Java. Again the RAF was allocated eight seats in one Lodestar. These were earmarked for Wng Cmmdr Maguire, Sdn Ldr Brooker, the injured Plt Off Watson, who had been collected from hospital, Sgt Sandeman Allen (who had also suffered a head injury in the motor accident) and Sgt Hardie, who was still suffering from ear trouble. Lot-drawing among the other pilots for the remaining seats brought allocations for Sgts King and Fairburn, while Plt Offs Fitzherbert and Bainbridge, and Sgt Porter were to standby in case there should be sufficient room for them. The aircraft was crammed with very senior Dutch officials, together with their families, and the pilot was very anxious to get away.

Wng Cmmdr Maguire discovered that the cargo holds were being loaded with luggage and got out of the aircraft to try and persuade the ground crew to off-load this to let more pilots aboard. The engines were running and a crowd of people, anxious to board the aircraft, were being held back by guards with fixed bayonets. Whilst the Wing Commander was arguing with the ground crew, someone closed the door and the Lodestar taxied out and took off! Sgt Fairburn was also left behind, having gained an allocation in the draw, he and fellow Australian Tom Young had retired to have a farewell drink and meal, but, on returning to Andir, found that the aircraft had already departed. Meanwhile the remains of the squadron had been ordered to Tasikmalaja from Andir, but bad weather and darkness prevented them completing the flight and they landed again at Andir to await morning.

end of extract from Bloody Shambles

Back at home :- Java falls to the Japanese and we hear no more news until 18th March when we thankfully hear from Peter by cable that he is safe in Perth, Australia - that is followed by a further cable on 20th March from Melbourne.

We hear no more direct news from Peter until 27th March 1942 when it is announced in all the Evening papers that he has been awarded a Bar to his D.F.C. for his gallant and cheerful work, leading his Squadron (No. 232) against the Japanese in Singapore and the Dutch East Indies. Another proud day for the family.

“Bar to the Distinguished Flying Cross - Acting Squadron Leader Richard Edgar Peter Brooker D.F.C. (39931) No 232 Squadron. This officer has continuously led the squadron into action against largely superior numbers of enemy aircraft at Singapore and in the Netherlands East Indies. He has displayed gallantry, determination and cheerfulness in the face of heavy odds.”

from the fourth Supplement to The London Gazette of Tuesday 24th March 1942; Friday 27th March 1942

“Flier who “cheerfully faced great odds” - A Squadron Leader who combined gallantry and determination with cheerfulness even at Singapore and in the Dutch East Indies despite superior numbers of enemy aircraft has been awarded the Bar to the D.F.C. He is acting Squadron Leader Richard E.P. Brooker D.F.C. of No 232 Squadron and it is stated he continuously led his squadron against heavy odds. His home is at Ashtead.” the Evening News, Friday 27th March 1942

“Cheerful Squadron Leader Beat Odds -- A Squadron Leader who combined gallantry and determination with cheerfulness, even at Singapore and in the Netherlands East Indies, has just been awarded the bar to the D.F.C. He is Acting Squadron Leader Richard Edgar Peter Brooker D.F.C. (232 Squadron) and it is stated he continuously led his squadron into action against numerically stronger enemy aircraft. Squadron-Leader Brooker, whose home is at Ashtead, was educated at the Royal Masonic School and commissioned in 1937” Evening Star 27.3.42

“R.A.F. Awards. Gallantry against the enemy. The King has approved the following awards in recognition of gallantry displayed in flying against the enemy:- Bar to the D.F.C. - Atg Sq Ldr. R.E.P.Brooker D.F.C. 232 Sq He has continuously led the squadron into action against largely superior numbers of enemy aircraft at Singapore and the Netherlands East Indies. He has displayed gallantry, determination and cheerfulness in the face of heavy odds.” The Times, 28th March 1942

Acting Squadron Leader Richard Edgar Peter Brooker (232 Squadron) has been awarded a bar to his D.F.C. Born at Chessington in 1918. Squadron Leader Brooker now lives at Ashtead. He was educated at the Royal Masonic School Bushey and was commissioned in 1937. He was awarded the D.F.C. in May last year when it was stated that since taking command of his squadron he had greatly assisted in the brilliant work done by his men. The bar to his D.F.C. is awarded for his continuous leadership of the squadron into action against largely superior numbers of enemy aircraft at Singapore and the Netherlands East Indies. ‘He has displayed gallantry, determination and cheerfulness in the face of heavy odds’ states the official citation.” The Surrey Advertiser

AWARD FOR ASHTEAD MAN a squadron leader who combined gallantry and determination with cheerfulness even at Singapore and in the Netherlands East Indies has been awarded the bar to the D.F.C.

He is Acting Squadron Leader Richard Edgar Peter Brooker (232 Squadron) and it is stated that he continuously led his squadron into action against numerically stronger enemy aircraft.

Squadron Leader Brooker, whose home is at ‘Little Hunstan’ Ottways Lane Ashtead, was educated at the Royal Masonic School, his father who has been dead for 18 years being a mason. He was a keen scholar and very fond of games, and in his last year at school he went with a school team to play hockey against German teams. On leaving school he wanted to fly and instead of going to a university he joined the R.A.F.

His grandfather, Mr. R.C. Brooker is still living in Ashtead, being over 80 years if age. He was the headmaster of Ashtead Church of England School for a number of years and was also Clerk to the old Ashtead Parish Council.

In July of last year, Squadron Leader Brooker went to the investiture at Buckingham Palace where the King awarded him the D.F.C. He is 23 years of age and was commissioned in 1937 He did duty during the whole of the Battle of Britain.” from the Epsom and Ewell Herald 3.4.42

The investiture was at 10.15am on 19th October 1943

A tribute from one of 232 Squadron - quoted in a letter received from Byng (S/Ldr A.W.Ridler) from Columbo in April 1942

“I met a bloke called Cooper-Slipper yesterday, who had been in Peter’s squadron in the Far East - and what he didn’t say about that brother of yours is nobody’s business: ‘A born leader who has the whole-hearted respect of his Squadron - who never claimed a victory, preferring to give it to others, who cannot be shaken by anything and leads his Squadron into whatever trouble may have developed, whatever the odds.’ In fact Cooper-Slipper gave him such a build-up I just stood by and gaped til he had finished. Even the bloke with whom I am sharing a room has worked with Peter - they were on the same job, the one for which Peter was rushed out from England.

Yes I guess A.M. will appreciate the amount of thought that went before R.E.P’s joining the R.A.F. I should be seeing him soon - everything that turns up I check up in case he’s with them - but no luck so far - and I know why. He’s first man in and means to be not out at the finish.”

7th March 1942 Peter reached Australia (Perth), Melbourne 17th March and back to Perth 23rd March where he joined 77 R.A.A.F. Squadron Pearce. On arrival in Australia his estimated flying hours were 1300 hours England, plus 100 hours Singapore/Sumatra?Java. His log book and all personal belongings had to be abandoned in Singapore when Japanese invaded.

26th April 1942 he joined No 76 R.A.A.F. Squadron at Townsville, flying Kittyhawks, helping train R.A.A.F. squadron etc. with Commander St. Vincent

Letter to his mother from Townsville:-

No 76 Sqdn

R.A.A.F. Australia

2nd July 1942

Dear Mother,

Here is a letter to you which will be very belated but I’ll tell you what news there is here now. Of course there are thousands of questions I’d like to ask you about everybody at home but I’m looking forward to one of your letters catching up with me in the near future and then I trust I get plenty of news. I expect quite a lot of your mail will never reach me but I’m hoping for a good bundle soon.

I’ll just run through a few dates for you about my little sojourn in the Far East. As you may have guessed, as for a rest it was to say the least a change and I don’t know whether you received any of the letters I posted from there but in case you didn’t I arrived there on Dec 14th, just a month after leaving. I did a stooge job for a bit sitting on the ground, but then some of the old friends I flew so much with in England arrived and, the C.O. being shot down in his first battle, I took it over. From then on I was pretty busy. I stayed in Singapore until Feb 8th, which was pretty late, then flew to Palembang.